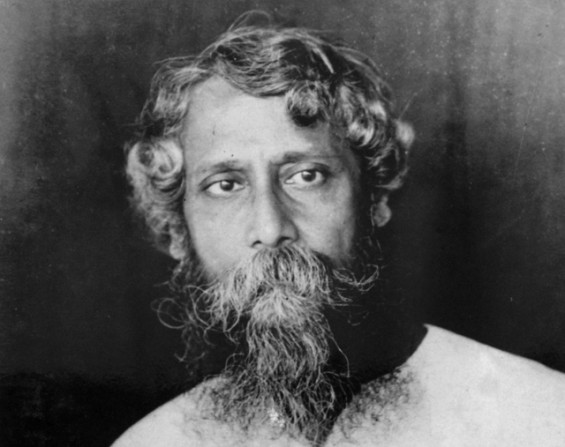

Here is a lecture Rabindranath Tagore delivered at the Calcutta university back in 1922, followed by another one by Leonard Elmhirst, who had joined Tagore for rural reconstruction efforts in Eastern India in the 1920s. Elmhirst, the agriculturist, concentrated on how the city takes all and returns little or nothing of real value to the soil’. Tagore, the humanist, talked about the importance of replenishing what you take from society as well as what you take from the soil.

Here is a lecture Rabindranath Tagore delivered at the Calcutta university back in 1922, followed by another one by Leonard Elmhirst, who had joined Tagore for rural reconstruction efforts in Eastern India in the 1920s. Elmhirst, the agriculturist, concentrated on how the city takes all and returns little or nothing of real value to the soil’. Tagore, the humanist, talked about the importance of replenishing what you take from society as well as what you take from the soil.

Tagore’s observations a century ago, appears eerily relevant even today.

The standard of living in modern civilization has been raised far higher than the average level of our necessity. The strain which this entails serves at the outset to increase our physical and mental alertness. The claim upon our energy accelerates growth. This in its turn produces activity that expresses itself by raising life’s standard still higher.

When this standard attains a degree that is a great deal above the normal it encourages the passion of greed. The temptation of an inordinately high level of living, which was once confined only to a small section of the community, becomes widespread. The burden is sure to prove fatal to the civilization which puts no restraint upon the emulation of self-indulgence.

In the geography of our economic world the ups and downs produced by inequalities of fortune are healthy only within a moderate range. In a country divided by the constant interruption of steep mountains no great civilization is possible because in such places the natural flow of communication is always difficult. Like mountains, large fortunes and the enjoyment of luxury are also high walls of segregation; they produce worse divisions in society than any physical barriers.

Where life’s simple wealth does not become too exclusive, owners of individual property find no great difficulty in acknowledging their communal responsibility. In fact wealth can even become the best channel for social communication. In former days in India public opinion levied heavy taxes upon wealth and most of the public works of the country were voluntarily contributed by the rich. The water supply, medical help, education and amusement were naturally maintained by men of property through a spontaneous sense of mutual obligation. This was made possible because the limits set to individual right of self-indulgence were narrow and surplus wealth easily followed the channel of social responsibility. In such a society civilization was supported by strong pillars of property, and wealth gave opportunity to the fortunate for self-sacrifice.

But, with the rise of the standard of living, property changes its aspect. It shuts the gate of hospitality which is the best means of social communication. Its owners display their wealth in an extravagance which is self-centred. This creates envy and irreconcilable class division. In other words property becomes anti-social.

But, with the rise of the standard of living, property changes its aspect. It shuts the gate of hospitality which is the best means of social communication. Its owners display their wealth in an extravagance which is self-centred. This creates envy and irreconcilable class division. In other words property becomes anti-social.

Because property itself, with what is called material progress, has become intensely individualistic, the method of gaining it has become a matter of science and not of social ethics. Property and its acquisition break social bonds and drain the life sap of the community. The unscrupulousness involved plays havoc the world over and generates a force that can coax or coerce peoples to deeds of injustice and wholesale horror.

The forest fire feeds upon the living world from which it springs till it exhausts itself completely along with its fuel. When a passion like greed breaks loose from the fence of social control it acts like that fire, feeding upon the life of society. The end is annihilation. It has ever been the object of the spiritual training of man to fight those passions that are anti-social and to keep them chained. But lately abnormal temptation has set them free and they are fiercely devouring all that is affording them fuel.

But there are always insects in our harvest field which, in spite of their robbery, tend to leave a sufficient surplus for the tillers of the soil, so that it does not pay us to try to exterminate them altogether. But when some pest, that has an enormous power of self multiplication, attacks our total food crop, we must consider this a great calamity. In human society, in normal circumstances, there are many causes that make for wastage, yet it does not cost us much to ignore them.

But today the blight that has fallen upon our social life and its resources is disastrous because it is not restricted within reasonable limits. This is an epidemic of voracity that has infected the total area of civilization. We all claim our right, and freedom, to be extravagant in our enjoyment if we can afford it. Not to be able to waste as much upon myself as my rich neighbour does merely proves a poverty in myself of which I am ashamed, and against which my women folk, and other dependents, naturally cherish their own grievance.

Ours is a society in which, through its tyrannical standard of respectability, all the members are goading each other to spoil themselves to the utmost limit of their capacity. There is a continual screwing up of the ideal level of convenience and comfort, the increase in which is proportionately less than the energy it consumes. The very shriek of advertisement itself, which constantly accompanies the progress of unlimited production, involves the squandering of an immense quantity of material and of life force which merely helps to swell the sweepings of time.

Civilization today caters for a whole population of gluttons. An intemperance, which could safely have been tolerated in a few, has spread its contagion to the multitude. This universal greed, which now infects us all, is the cause of every kind of meanness, of cruelty and of lies in politics and commerce, and vitiates the whole human atmosphere. A civilization, which has attained such an unnatural appetite, must, for its continuing existence, depend upon numberless victims.

These are being sought in those parts of the world where human flesh is cheap. In Asia and Africa a bartering goes on through which the future hope and happiness of entire peoples is sold for the sake of providing some fastidious fashion with an endless supply of respectable rubbish.

The consequence of such a material and moral drain is made evident when one studies the condition manifested in the grossness of our cities and the physical and mental anaemia of the villages almost everywhere in the world. For cities inevitably have become important. The city represents energy and materials concentrated for the satisfaction of an exaggerated appetite, and this concentration is considered to be a symptom of civilization. The devouring process of such an abnormality cannot be carried on unless certain parts of the social body conspire and organize to feed upon the whole. This is suicidal; but, before a gradual degeneracy ends in death, the disproportionate enlargement of the particular portion looks formidably great. It conceals the starved pallor of the entire body. The illusion of wealth becomes evident because certain portions grow large on their robbery of the whole.

A living relationship, in a physical or in a social body, depends upon sympathetic collaboration and helpfulness between the various individual organs or members. When a perfect balance of interchange begins to operate, a consciousness of unity develops that is no longer easy to obstruct. The resulting health or wealth are both secondary to this sense of unity which is the ultimate end and aim, and a creation in its own right. Whenever some sectarian ambition for power establishes a dominating position in life’s republic, the sense of unity, which can only be generated and maintained by a perfect rhythm of reciprocity between the parts is bound to be disturbed.

In a society where the greed of an individual or of a group is allowed to grow uncontrolled, and is encouraged or even applauded by the populace, democracy, as it is termed in the West, cannot be truly realized. In such an atmosphere a constant struggle goes on among individuals to capture public organizations for the satisfaction of their own personal ambition.

Thus democracy becomes like an elephant whose one purpose in life is to give joy rides to the clever and to the rich. The organs of information and expression, through which opinions are manufactured, and the machinery of administration, are openly or secretly manipulated by the prosperous few, by those who have been compared to the camel which can never pass through the needles eye, that narrow gate that leads to the kingdom of ideals.

Such a society necessarily becomes inhospitable, suspicious, and callous towards those who preach their faith in ideals, in spiritual freedom. In such a society people become intoxicated by the constant stimulation of what they are told is progress, like the man for whom wine has a greater attraction than food.

Villages are like woman. In their keep is the cradle of the race. They are nearer to nature than the towns and are therefore in closer touch with the fountain of life. They have the atmosphere which possesses a natural power of healing. Like woman they provide people with their elemental needs, with food and joy, with the simple poetry of life and with those ceremonies of beauty which the village spontaneously produces and in which she finds delight. But when constant strain is put upon her through the extortionate claims of ambition, when her resources are exploited through the excessive stimulus of temptation, then she becomes poor in life. Her mind becomes dull and uncreative; and, from her time honoured position as the wedded partner of the city, she is degraded to that of maid servant. The city, in its intense egoism and pride, remains blissfully unconscious of the devastation it is continuously spreading within the village, the source and origin of its own life, health and joy.

True happiness is not at all expensive. It depends upon that natural spring of beauty and of life, harmony of relationship. Ambition pursues its own path of self-seeking by breaking this bond of harmony, digging gaps, creating dissension. Selfish ambition feels no hesitation in trampling under foot the whole harvest field, which is for all, in order to snatch away in haste that portion which it craves. Being wasteful it remans disruptive of social life and the greatest enemy of civilization.

In India we had a family system of our own, large and complex, each family a miniature society in itself. Ido not wish to discuss the question of its desirability, but its rapid decay in the present day clearly points out the nature and process of the principle of destruction which is at work in modern civilization. When life was simple, needs normal, when selfish passions were under control, such a domestic life was perfectly natural and truly productive of happiness. The family resources were sufficient for all. Claims from one or more individuals of that family were never excessive. But such a group can never survive if the personal ambition of a single member begins separately to clamour for a great deal more than is absolutely necessary for him. When the determination to augment private possession, and to enjoy exclusive advantage, runs ahead of the common good and of general happiness, the bond of harmony, which is the bond of creation, must give way and brothers must separate nay even become enemies.

This passion of greed that rages in the heart of our present civilization, like a volcanic flame of fire, is constantly struggling to erupt in individual bloatedness. Such eruptions must disturb mans creative mind. The flow of production which gushes from the cracks rent in society gives the impression of a hugely indefinite gain. We forget that the spirit of creation can only evolve out of our own inner abundance and so add to our true wealth. A sudden increase in the flow of production of things tends to consume our resources and requires us to build new storehouses. Our needs, therefore, which stimulate this increasing flow, must begin to observe the limitation of normal demand. If we go on stoking our demands into bigger and bigger flames the conflagration that results will no doubt, dazzle our sight, but its splendour will leave on the debit side only a black heap of charred remains.

This passion of greed that rages in the heart of our present civilization, like a volcanic flame of fire, is constantly struggling to erupt in individual bloatedness. Such eruptions must disturb mans creative mind. The flow of production which gushes from the cracks rent in society gives the impression of a hugely indefinite gain. We forget that the spirit of creation can only evolve out of our own inner abundance and so add to our true wealth. A sudden increase in the flow of production of things tends to consume our resources and requires us to build new storehouses. Our needs, therefore, which stimulate this increasing flow, must begin to observe the limitation of normal demand. If we go on stoking our demands into bigger and bigger flames the conflagration that results will no doubt, dazzle our sight, but its splendour will leave on the debit side only a black heap of charred remains.

When our wants are moderate, the rations we each claim do not exhaust the common store of nature and the pace of their restoration does not fall hopelessly behind that of our consumption. This moderation leaves us leisure to cultivate happiness, that happiness which is the artist soul of the human world, and which can create beauty of form and rhythm of life. But man today forgets that the divinity within him is revealed by the halo of this happiness.

The Germany of the period of Goethe was considered to be poverty stricken by the Germany of the period of Bismarck. Possibly the standard of civilization, illuminated by the mind of Plato or by the life of the Emperor Asoka, is underrated by the proud children of modern times who compare former days with the present age of progress, an age dominated by millionaires, diplomats and war lords.

Many things that are of common use today were absolutely lacking in those days. But are the people that lived then to be pitied by the young of our day who enjoy so much more from the printing press but so much less from the mind?

I often imagine that the moon, being smaller in size than the earth, produced the condition for life to be born on her soil earlier than was possible on the soil other companion. Once she too perhaps had her constant festival, of colour, of music and of movement; her store-house was perpetually replenished with food for her children. Then in course of time some race was born to her that was gifted with a furious energy of intelligence, and that began greedily to devour its own surroundings. It produced beings who, because of the excess of their animal spirit, coupled with intellect and imagination, failed to realize that the mere process of addition did not create fulfilment; that mere size of acquisition did not produce happiness; that greater velocity of movement did not necessarily constitute progress and that change could only have meaning in relation ,to some clear ideal of completeness.

Through machinery of tremendous power this race made such an addition to their natural capacity for gathering and holding, that their career of plunder entirely outstripped natures power for recuperation. Their profit makers dug big holes in the stored capital of the planet. They created wants which were unnatural and provision for these wants was forcibly extracted from nature.

When they had reduced the limited store of material in their immediate surroundings they proceeded to wage furious wars among their different sections, each wanting his own special allotment of the lions share. In their scramble for the right of self-indulgence they laughed at moral law and took it to be a sign of superiority to be ruthless in the satisfaction each of his own desire. They exhausted the water, cut down the trees, reduced the surface of the planet to a desert, riddled with enormous pits, and made its interior a roiled pocket, emptied of its valuables.

At last one day the moon, like a fruit whose pulp had been completely eaten by the insects which it had sheltered, became a hollow shell, a universal grave for the voracious creatures who insisted upon consuming the world into which they had been born. In other words, they behaved exactly in the way human beings of today are behaving upon this earth, fast exhausting their store of sustenance, not because they must live their normal life, but because they wish to live at a pitch of monstrous excess.

[youtube Kci0WEpn5XI]

[youtube vo15sPIEOc0]

[youtube mCu0Sl8NG1M]

[youtube yHxQY20oPN8]

[youtube FbK713wXrqk]

[youtube CmoYdsPQuU4]

[youtube 5e0VUbgZVDY]

[youtube pMmGFROQIE8]

Mother Earth has enough for the healthy appetite other children and something extra for rare cases of abnormality. But she has not nearly sufficient for the sudden growth of a whole world of spoiled and pampered children.

Man has been digging holes into the very foundations not only of his livelihood but of his life. He is now feeding upon his own body. The reckless waste of humanity which ambition produces is best seen in the villages where the light of life is gradually being dimmed, the joy of existence dulled, and the natural bonds of social communion are being snapped every day. It should be our mission to restore the full circulation of life’s blood into these martyred limbs of society; to bring to the villagers health and knowledge; a wealth of space in which to live, a wealth of time in which to work, to rest and enjoy mutual respect which will give them dignity; sympathy which will make them realize their kinship with the world of men and not merely their position of subservience.

Streams, lakes and oceans are there on this earth. They exist not for the hoarding of water exclusively each within its own area. They send up the vapour which forms into clouds and helps in aside distribution of water. Cities have a special function in maintaining wealth and knowledge in concentrated forms of opulence, but this should not be for their own exclusive sake; they should not magnify themselves, but should enrich the entire society. They should be like the lamp post, for the light it supports must transcend its own limits. Such a relationship of mutual benefit between the city and the village remains strong only so long as the spirit of co-operation and self-sacrifice is a living ideal in society as awhile. When some universal temptation overcomes this ideal when some selfish passion finds ascendancy then a gap is formed and widened between them. The mutual relationship between city and village becomes that of exploiter and victim. This is a form of perversity in which the body becomes its own enemy. The termination is death.

We have started in India, in connection with Visva-Bharati, a kind of village work the mission of which is to retard this process of race suicide. If l try to give you details of the work the effort will look small. But we are not afraid of this appearance of smallness, for we have confidence in life. We know that if, as a seed, smallness represents the truth that is in us, it will overcome opposition and conquer space and time. According to us the poverty problem is not so important. It is the problem of unhappiness that is the great problem.

The search for wealth which is the synonym for the production and collection of things can make use of men ruthlessly can crush life out of the earth and for a time can flourish. Happiness may not compete with wealth in its list of needed materials, but it is final, it is creative therefore it has its own source of riches within itself. Our object is to try to flood the choked bed of village life with streams of happiness. For this the scholars, the poet, the musicians, the artists as well as the scientists have to collaborate, have to offer their contribution.

Otherwise they live like parasites, sucking life from the country people, and giving nothing back to them. Such exploitation gradually exhausts the soil of life, the soil which needs constant replenishing by the return of life to it through the completion of the cycle of receiving and giving back.

The writer of the following paper (Elmhirst), who was in charge of the rural work in Visva-Bharati, forcibly drew our attention to this subject and made it clear to us that the civilization which allows its one part to exploit the rest without making any return is merely cheating itself into bankruptcy. It is like the foolish young man, who suddenly inheriting his fathers business, steals his own capital and spends it in a magnificent display of extravagance. He dazzles the imagination of the onlookers, he gains applause from his associates in his dissipation, he becomes the most envied man in his neighbourhood till the morning when he wakes up, in surprise, to a state of complete indigence.

Most of us who try to deal with the poverty problem think of nothing else but of a greater intensive effort of production, forgetting that this only means a greater exhaustion of materials as well as of humanity, and this means giving a still better opportunity for profit to the few at the cost of the many. But it is food which nourishes and not money. It is fullness of life which makes us happy and not fullness of purse. Multiplying materials intensifies the inequality between those who have and those who have not. This is the worst wound from which the social body can suffer. It is a wound through which the body is bled to death!

1922